CT, ultrasound, and MRI each serve distinct roles in detecting hernias—though physical examination remains the gold standard for clinically apparent cases, imaging becomes essential when symptoms are unclear, complications are suspected, or surgical planning requires precise measurements. Approximately 32.5 million people worldwide have a hernia at any given time, and 27% of men will develop an inguinal hernia during their lifetime. Understanding when imaging adds clinical value—versus when it represents unnecessary testing—empowers patients to make informed decisions about their diagnostic pathway.

Physical examination detects most hernias without imaging

The visible bulge that most people associate with hernias is often all a physician needs to make a diagnosis. Current international guidelines, including those from the American Hernia Society and European Hernia Society, recommend against routine imaging for clinically apparent groin hernias. A skilled physical examination—with the patient standing and performing the Valsalva maneuver (bearing down)—can identify the telltale impulse of tissue pushing through the abdominal wall.

This exam-first approach isn’t just tradition. Research shows that up to 50% of pre-surgical imaging may be unnecessary for patients with palpable hernias that both the referring physician and surgeon can detect. The Choosing Wisely campaign specifically advises against routine imaging when clinical findings are clear, noting that positive imaging alone rarely changes the surgical decision.

However, several scenarios demand the superior detail that imaging provides. When patients report groin or abdominal pain without a palpable bulge—called an “occult hernia”—ultrasound serves as the first-line investigation. Obesity significantly limits physical examination, as abundant subcutaneous fat can mask deeply seated defects. Women present a particular diagnostic challenge because their inguinal hernias tend to cause subtle pelvic pain rather than obvious bulging, leading to frequent misdiagnosis as gynecological conditions. Post-surgical evaluation for recurrent hernias and complex incisional defects almost always warrant imaging to assess mesh position and identify the precise location of any new weakness.

Ultrasound offers radiation-free, dynamic visualization

For groin hernias specifically, ultrasound has emerged as the preferred first-line imaging modality. Modern high-frequency linear transducers (7.5-10 MHz) achieve sensitivity of 86-96% and specificity of 77-96% for inguinal hernias. The technique’s greatest advantage lies in its dynamic capability—the sonographer can observe tissue movement in real time while the patient strains, stands, or changes position.

During a hernia ultrasound, the technologist applies gel to the skin and moves a handheld probe over the affected area. The examination typically takes 15-30 minutes. Patients should expect to perform the Valsalva maneuver repeatedly, sometimes while standing, to make intermittent or reducible hernias more visible. This dynamic assessment represents a significant advantage over CT scanning, which captures only a single moment in time.

Ultrasound excels at distinguishing hernia contents: fatty tissue appears relatively bright and compressible, while bowel loops display the characteristic layered “gut signature” with visible peristalsis. The presence of normal peristalsis is reassuring—aperistaltic (motionless) bowel within a hernia raises concern for strangulation. Sonographic findings that suggest incarceration include free fluid in the hernia sac (present in 91% of incarcerated cases versus only 3% of uncomplicated hernias), bowel wall thickening greater than 3mm, and inability to reduce the hernia with gentle probe pressure.

The technique’s limitations include operator dependence—accuracy varies significantly based on the sonographer’s expertise—and reduced penetration in obese patients. Ultrasound also struggles with deep pelvic hernias like obturator and sciatic types, where CT provides superior visualization.

CT scanning reveals complications and guides surgical planning

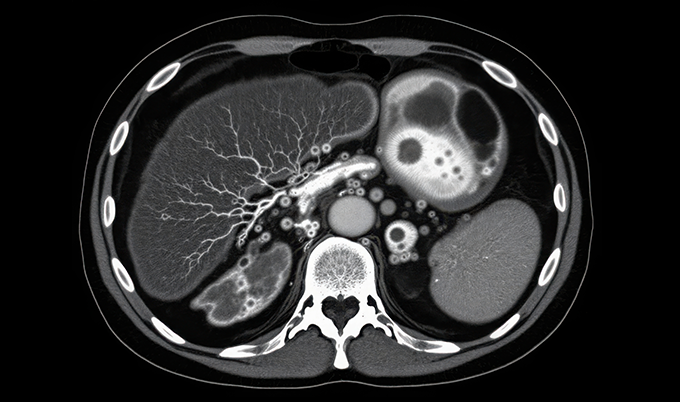

Computed tomography has become the workhorse for complex hernia evaluation, emergency presentations, and pre-operative planning. While sensitivity for routine hernia detection (68-86%) falls slightly below ultrasound, CT’s specificity reaches 90-98% and provides unmatched detail about anatomical relationships, hernia contents, and complications.

The CT examination itself takes only 10-15 minutes, though contrast preparation may extend the total appointment to an hour. Patients lie on a table that slides through the scanner’s donut-shaped opening. The technologist may request breath-holding and Valsalva maneuvers—studies show hernias measure up to 28% larger on Valsalva CT compared to resting images, with better visibility in 73-82% of cases.

CT imaging identifies hernia contents with remarkable precision: mesenteric fat appears as low-density areas with negative Hounsfield units, bowel loops show as tubular structures often containing air-fluid levels, and enhanced vessels radiating from the defect indicate mesenteric involvement. For surgical planning, radiologists measure the defect in two planes and calculate critical metrics like the Rectus-to-Defect Ratio—when this ratio falls below 1.5, over half of patients will require component separation techniques rather than simple repair.

The imaging findings that demand emergency surgical intervention include absent or reduced bowel wall enhancement (indicating ischemia), the “C-shaped” closed-loop configuration suggesting bowel twisting, mesenteric vessel swirling at the hernia orifice, and pneumatosis intestinalis (air within the bowel wall). CT demonstrates 83-100% sensitivity for detecting strangulation, with accuracy reaching 96% for multi-detector technology.

MRI provides highest accuracy for hidden hernias

When ultrasound fails to explain persistent groin symptoms, MRI offers the highest diagnostic accuracy for occult inguinal hernias: 91-100% sensitivity and 92-97% specificity. The modality’s superior soft tissue contrast can differentiate true hernias from sports-related muscle injuries, adductor strains, and other mimics that cause similar pain patterns.

MRI scans take longer (30-90 minutes) and cost more than alternatives, but they expose patients to no ionizing radiation—an important consideration for young patients or those requiring repeated imaging. The examination occurs within a tunnel-shaped scanner, and patients should alert staff about claustrophobia concerns; mild sedation, eye masks, and music through headphones can improve tolerance. Modern wide-bore machines (70cm diameter) accommodate larger patients and reduce anxiety.

The American College of Radiology rates MRI as “usually appropriate” for groin hernia evaluation alongside ultrasound and CT, particularly endorsing it when initial ultrasound is negative but clinical suspicion persists. Dynamic MRI with Valsalva maneuver achieves accuracy of 98% with excellent interrater agreement.

Emergency symptoms require immediate CT evaluation

Certain clinical presentations bypass the usual diagnostic algorithm entirely, mandating emergency CT with intravenous contrast. A previously reducible hernia that suddenly becomes irreducible with severe pain suggests incarceration—tissue trapped outside the abdominal cavity without blood flow compromise. When incarceration progresses to strangulation, the blood supply is cut off entirely, and bowel necrosis can develop within hours.

Red flag symptoms requiring immediate emergency department evaluation include a hernia bulge that turns red, purple, or dark; sudden onset of severe pain that rapidly intensifies; nausea and vomiting; inability to pass gas or have bowel movements; and fever. These findings carry mortality rates of 13-40% for certain hernia types if diagnosis is delayed.

Post-bariatric surgery patients presenting with acute abdominal pain represent another urgent imaging indication. Internal hernias—tissue protruding through abnormal openings within the abdominal cavity—complicate 1-9% of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures and cause closed-loop obstruction with high mortality if unrecognized. CT findings include clustered bowel loops with converging mesenteric vessels and the characteristic “swirl sign” of twisted vasculature.

Different hernia types require tailored imaging approaches

The optimal imaging strategy depends heavily on hernia location. Inguinal hernias (75-80% of all hernias) generally require only ultrasound when imaging is indicated, with CT reserved for complications or surgical planning. Femoral hernias, which carry higher strangulation risk due to their narrow neck, benefit from CT’s ability to differentiate them from inguinal hernias—a distinction that affects surgical approach.

Incisional hernias developing at previous surgical sites occur in 2-20% of abdominal operations and frequently involve multiple defects (“Swiss cheese” pattern). CT with Valsalva maneuver provides the comprehensive mapping surgeons need, including loss of domain calculations—when the hernia sac volume exceeds 20% of total abdominal volume, patients face elevated risk of respiratory failure and recurrence after repair.

Hiatal hernias involving the diaphragm follow different imaging rules entirely. Barium swallow studies remain the gold standard, with the patient drinking contrast while fluoroscopy captures the gastroesophageal junction’s relationship to the diaphragm. CT can detect large hiatal hernias but misses smaller sliding defects.

Deep pelvic hernias through the obturator foramen or sciatic notch rarely produce palpable findings and require CT or MRI for diagnosis. These rare but dangerous hernias typically affect thin, elderly women and may present only with referred pain to the medial thigh (Howship-Romberg sign).

Preventive CT screening can incidentally detect hernias

Full-body CT screening, though not specifically designed for hernia detection, examines the abdomen and pelvis with sufficient detail to identify abdominal wall defects as “anatomical abnormalities.” Services like Craft Body Scan’s Full Body Scan ($2,495) include comprehensive abdominal imaging that can reveal previously undiagnosed hernias alongside other findings—though most patients undergo such screening for cancer and cardiac disease detection rather than hernia concerns.

The self-pay, direct-to-consumer model offers accessibility advantages: no referral is required, appointments are available without insurance authorization delays, and results reach patients within 5-10 business days. For individuals with vague abdominal symptoms or those seeking baseline health assessment, incidental hernia detection represents one of many potential findings from comprehensive body scanning.

Preparing for your hernia scan maximizes diagnostic accuracy

Preparation requirements vary by imaging modality. Ultrasound typically requires no special preparation, though patients may be asked to arrive with a full bladder for pelvic evaluation. CT scans with contrast require disclosure of kidney problems, contrast allergies, and metformin use; some facilities request 2-4 hour fasting, though recent evidence suggests this may not be strictly necessary. MRI demands careful metal screening—pacemakers, cochlear implants, and certain metal implants may contraindicate the examination.

For all scan types, wearing comfortable, loose-fitting clothing without metal components speeds the process. Informing the technologist about previous surgeries, current symptoms, and the behavior of any bulge (when it appears, whether it reduces) helps guide the examination technique.

What imaging results mean for your treatment path

Radiology reports follow a standard structure: indication (why the test was ordered), technique, comparison to prior studies, detailed findings, and impression (the summary conclusion). Patients should understand key terminology: “reducible hernia” means the tissue returns to normal position with gentle pressure, “incarcerated” indicates trapped contents, and “strangulated” describes compromised blood supply requiring emergency surgery.

For uncomplicated hernias causing minimal symptoms, watchful waiting may be appropriate—particularly for men with inguinal hernias. However, approximately two-thirds of patients eventually require surgical repair within ten years. Women with inguinal hernias face higher complication rates and typically receive recommendations for earlier intervention.

When surgery is indicated, imaging findings directly influence the approach. Laparoscopic techniques using 2-3 small incisions offer faster recovery (2-4 weeks versus 4-6 weeks for open surgery), less post-operative pain, and lower infection rates. The detailed anatomical mapping from CT helps surgeons select between laparoscopic and open approaches, plan mesh sizing with appropriate 5cm overlap on all sides, and identify previous mesh requiring removal.

Conclusion

Hernia imaging represents a sophisticated diagnostic toolkit where the right test depends entirely on clinical context. Physical examination remains sufficient for most clinically apparent hernias, but ultrasound provides excellent first-line imaging for groin hernias when needed, CT excels in emergency settings and surgical planning, and MRI offers the highest accuracy for occult or recurrent cases. Understanding these distinctions—and recognizing emergency symptoms that demand immediate imaging—allows patients to navigate their diagnostic journey with appropriate urgency while avoiding unnecessary testing. The 43% of preventive scan recipients who discover early disease findings underscore the value of comprehensive imaging, even when hernias aren’t the primary concern.